On the Origins of Algorithmic Progress in AI

Insights from our new paper on the scale-dependence of algorithmic progress.

The world’s best AI researchers have been paid millions of dollars for their expertise. How much do their research breakthroughs impact AI progress compared to building bigger, more powerful datacenters? Our new paper titled On the Origins of Algorithmic Progress in AI suggests that the literature overestimates the role of algorithmic breakthroughs and underestimates the role of increased computing resources.

The sources of progress in AI capabilities are typically broken down into three distinct components:

Compute scaling counts the raw number of mathematical operations, or FLOPs, performed during model training. More FLOPs mean better performance. You can perform more total operations when you (1) have more total hardware or (2) run that hardware for longer.

Hardware efficiency quantifies the costs of each operation in monetary, energy, or time units. Better hardware efficiency implies more FLOPs can be performed for the same number of dollars, joules, or days.

Algorithmic efficiency encompasses the cleverness of the training procedure, quantifying the performance “bang” for each FLOP “buck.” Better algorithmic efficiency means you can achieve the same model performance while using fewer operations.

Typically, each of these components is treated as orthogonal to the others, such that improvements can be evaluated independently between sources of progress. For example, hardware efficiency (in FLOPs per dollar) improved 45x between 2013 and 2024. Because compute scale and hardware efficiency are considered independent, you can expect your hardware efficiency gains to be roughly that same 45x regardless of whether you have 10 GPUs or 10,000.1

Traditionally, algorithmic efficiency is also thought to be independent of compute scale. Whether you have 1015 FLOPs or 1025 FLOPs, the literature assumes that when researchers discover better training techniques, applying these algorithmic improvements should always yield the same multiplicative efficiency improvements – regardless of compute scale (e.g. 10x less compute at 1015 FLOPs and 1025 FLOPs alike). But is this a safe assumption?

Our new paper provides strong experimental evidence against this view. We find that algorithmic efficiency is compute scale-dependent: some algorithms provide increasing – not constant – efficiency returns to scale. We estimate that from 2012 to 2025, as much as 91% of efficiency gains depend on (historically exponential) compute scaling, meaning that if compute scaling had not occurred, algorithmic innovations alone would yield less than 10% of the efficiency improvements we measure today.

Our paper further examines the downstream implications of these findings while laying the theoretical foundations for analyzing algorithmic progress in light of this scale-dependence. In this post, we’ll cover:

How to quantify algorithmic progress in AI;

The stunning role of scale-dependence in this progress, as revealed by our experiments;

What questions remain to inform future research.

How do we quantify algorithmic progress in AI pre-training?

If you are familiar with the notion of an algorithm’s time-complexity, you’ve probably heard of Big-O notation, which gives us a concise language for capturing the asymptotic features of classical algorithms. Stating an algorithm has complexity O(n2) means you’ll need something like “the square of the input size” steps before terminating. Specifically, this notation is ideal when we care about runtime across varying input sizes, not the precise number of steps.

For AI algorithms, we need a different framework for comparison. Unlike traditional algorithms, in machine learning, a training algorithm doesn’t produce a correct answer from a fixed-size input. Instead, it utilizes some quantity of FLOPs to output a model with a given performance level. The relationship between FLOPs and performance are known as neural scaling laws, and they will help us define a framework for measuring algorithmic efficiency in machine learning. To help illustrate, we’ll call on our ever-reliable friends Alice and Bob.

Imagine Alice and Bob have two different training algorithms. Bob is given some fixed compute budget of 1020 FLOPs to use with his algorithm, and creates a model with some performance level. To analyze the efficiency improvements from Alice’s algorithm (or lack thereof), we can ask “how much more/less compute would Alice’s scaling law require to reach the same level of performance that Bob’s model achieved with 1020 FLOPs?” Perhaps Alice has a better algorithm which only needs 1019 FLOPs to reach performance parity with Bob’s model. In this case, we would say Alice’s algorithm achieves a 10x compute-equivalent gain (CEG) relative to Bob’s 1020 FLOPs model.

In the existing literature, including work from our lab, this CEG multiplier of 10x is assumed to hold no matter Bob’s compute budgets. We would assume, for example, that if Bob trained a 1025 FLOPs model, it would match Alice’s 1024 FLOPs model in performance. But in our paper, we show empirically that–just like the time complexity of a classical algorithm–the efficiency gain from an algorithmic innovation may depend on the compute scale. For example, it’s possible that when Bob uses 1015 FLOPs, Alice’s algorithm uses 10x less compute (1014 FLOPs) to reach performance parity; but when Bob uses 1020 FLOPs, Alice can get away with using 100x less (only 1018 instead of 1019 FLOPs). Efficiency gains are compute scale-dependent.

Using an expanded framework which allows for this scale-dependence, our paper further breaks down the algorithmic innovations of the past decade into those which do and don’t depend on compute scale – and quantifies how much each matters. We show that most progress has indeed come from steadily increasing compute budgets, which makes Alice’s algorithm appear to be more and more efficient by comparison to Bob’s. This is in contrast to the dominant view in the literature, where progress comes from steady innovations in Alice’s algorithm.

In the next section, we’ll outline the empirical results and methods that lead to this finding.

Scale-dependence (and a lot of compute) is all you need!

To rigorously test the efficiency gains from different algorithmic innovations, we use validation loss as our performance metric, which measures how well the model approximates the training data’s distribution. We ran two kinds of experiments: ablation experiments and scaling experiments.

Ablation experiments surgically remove targeted innovations from the training algorithms to measure their performance contributions. This isolates the role of specific algorithms.

Scaling experiments measure performance for different algorithms across different compute scales, deriving scaling laws in the process. This isolates the role of compute scale for a particular training algorithm.

Most of the algorithms we tested (e.g. optimizers, normalization, encodings) were scale-invariant changes. That is, they improved efficiency by a constant factor regardless of the size of the model trained. How do we know this? We tested a cluster of algorithms over a range of compute scales.2 When removing all of these algorithms at once, the change detected in our scaling law was the same percentage of compute across all compute scales.3 This provides strong evidence that these changes individually have scale-invariant efficiency improvements.4

However, two of the innovations we explored were strongly scale-dependent:

the transition from LSTM to Transformer architectures, and

the transition to Chinchilla-optimal scaling.

These innovations represented the overwhelming share of net efficiency improvements. Running scaling experiments between LSTMs and Transformer separately, we show that this architecture switch has scale-dependent efficiency improvements.5 As the compute budget for the LSTM increases, the potential compute savings of switching to a Transformer get larger and larger.

We also analytically explored changes in data-parameter balancing: when training large models, an inevitable tradeoff between the model size and the dataset size determines the total compute cost. Over time, our understanding of the optimal balance has improved. Kaplan et al. recommended tilting more heavily towards parameters, while later work from Hoffman et al. (known as “Chinchilla scaling”) advocated for a more balanced approach. We show that switching from Kaplan’s once state-of-the-art recommendation to the Chinchilla scaling yields increasing efficiency returns with compute scale. In other words, the cost of balancing incorrectly gets worse and worse with more compute.

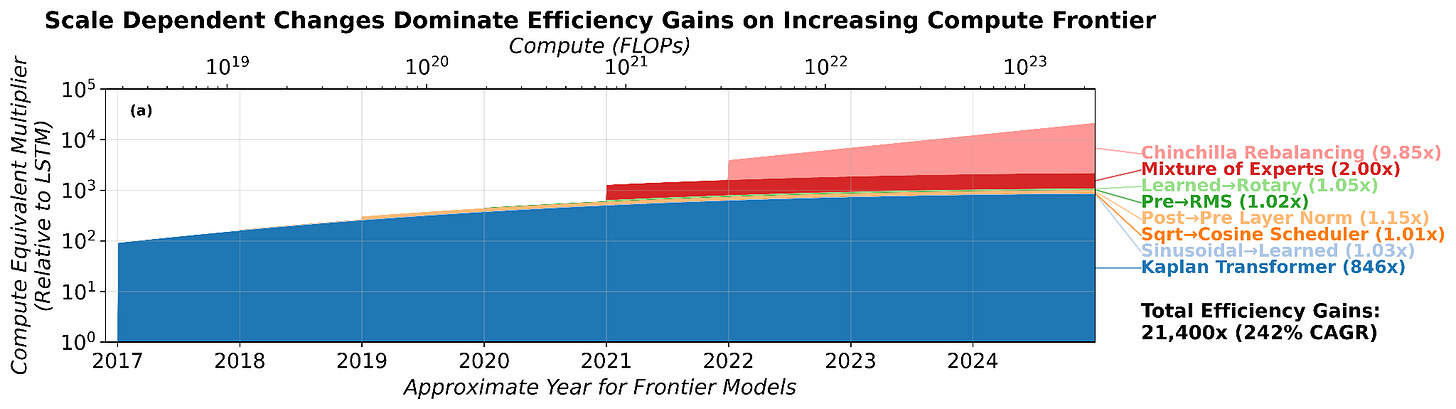

Although our experiments are done at small scales, we can extrapolate our findings to estimate the efficiency improvements across larger compute budgets. Research done by Epoch AI suggests that frontier compute levels have followed a pretty smooth exponential growth trend over time. Using these estimates, we create a detailed image of efficiency improvements over historical compute scales:

We recover 6,930x of the 22,000x improvement in algorithmic progress estimated by our previous paper with Epoch AI from 2012 through 2023. Though naively it may seem like we only capture one-third of total algorithmic progress, leaving 3x out of 22,000x unaccounted for means we account for more than 88% of total multiplicative efficiency gains.

We find that at 2025 frontier compute levels, 91% of measured algorithmic progress came from scale-dependent innovations. These gains would not have been reaped without increasing compute budgets, meaning models trained with less compute have seen less than 10% of this efficiency improvement.

Below you can see the precise breakdown of progress decomposed into specific innovations. The innovations are depicted starting when they were discovered, and the compute scale is determined by the trend of notable models in that year. The scale-invariant changes, despite their quantity, represent a small fraction of the efficiency gains by 2025. The large blue region represents the switch to Transformers, while the lighter red region represents Chinchilla rebalancing.

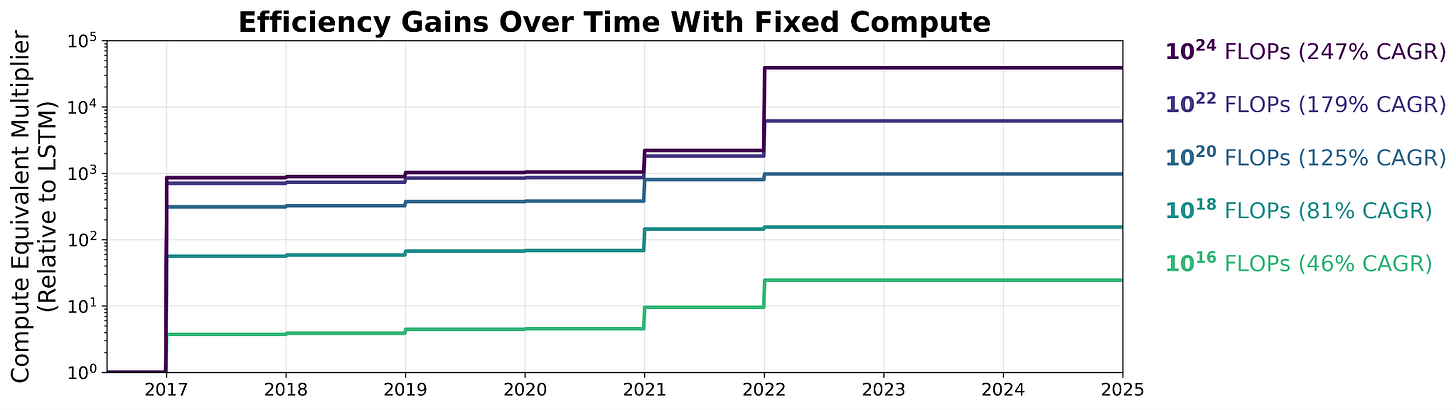

If models trained with less compute aren’t getting the same benefits, that has implications for the environment, science, and society more broadly. Smaller models use orders of magnitude less energy, and therefore fewer emissions.6 Smaller foundation models are the dominant option for scientific methodologies across disciplines. Smaller models are essential for private, local AI on personal devices. The figure below highlights the stark differences in efficiency gains across model compute scales. Models trained with 1016 FLOPs see less than 30x efficiency gains, while models trained with 1024 FLOPs reap more than 20,000x improvement! These are implications we hope to explore in future research.

How could we improve measures of algorithmic progress?

The framework we’ve proposed is an extension of the CEG framework from the existing literature. However, the notion of a compute equivalent gain admits two important limitations, both of which point to important future research on how we conceptualize algorithmic progress. In particular, CEG is (1) highly reference frame-dependent and (2) relies on choosing the right model performance metric.

Reference-Frame Dependence

Reference-frame dependence is a counterintuitive property that we elucidate in depth in the paper, and which only arises when efficiency improvements are scale-dependent. Importantly, this phenomenon does not occur for the kinds of efficiencies people usually reason about in everyday life, which are scale-independent.

To see the contrast, consider a familiar case where scale dependence is absent. Suppose you buy a new iPhone 16 and are told its battery efficiency is 10x better than the first iPhone. Then you hear that the iPhone 17 is 100x more efficient than the first iPhone. In that setting, it would be perfectly reasonable—and indeed unavoidable—to conclude that the iPhone 17 is about 10x more battery-efficient than the iPhone 16. Battery efficiency improvements compose transitively and can be compared without worrying about reference frames.

Algorithmic efficiency, as measured by compute-equivalent gains (CEGs), behaves differently when improvements are scale-dependent. In particular, it is possible to have a sequence of models trained with steadily increasing compute (e.g. progressively larger, otherwise unchanged Transformer models) where each model is no more compute-efficient than the previous one. Yet relative to a different reference algorithm, such as an LSTM, the same sequence can appear to exhibit continual efficiency gains. In this case, nothing about the training algorithm itself has improved; instead, increasing compute moves the model along a scaling curve where the gap to the reference algorithm’s scaling curve grows.

This creates the appearance of algorithmic progress without new innovations. Without explicitly running scaling and ablation experiments of the sort we do in the paper, simply observing improved performance at larger scales can lead the CEG framework to attribute efficiency gains to “algorithmic progress” that are in fact inherited from scale-dependent properties of earlier innovations.

Performance Metrics

When measuring model performance, we use cross-entropy loss as our metric, which is standard in the scaling law literature. It tells you how good your prediction is relative to the true data distribution. This subtly makes our performance metric “how well does my model fit the training data?” Algorithmic progress, however, encompasses more than the fitness of the model to the data.

Modern chatbots, for example, don’t want to approximate the exact pre-training distribution. Through reinforcement learning, large language models subtly augment their output distribution to mimic instruction following, obey safety guardrails, or emphasize chain-of-thought reasoning. Measuring performance in those domains is less straightforward, and is not well captured by the CEG framework without a clearly defined benchmark or fitness metric.

Moreover, many recent algorithmic innovations haven’t focused on pre-training at all. Instead, a large chunk of computing costs come from serving models, making the cost of inference also economically important. Lots of innovations focus on improving efficiency after the model is trained, with techniques like distillation and quantization targeting runtime efficiency and performance tradeoffs. (See here for some recent work from our lab on the pace of progress in these areas.)

Wrapping up

At MIT FutureTech, algorithmic progress has been a pillar of our research for many years, well beyond algorithms for machine learning. We’ve built the world’s largest database of algorithms, created a framework and a tool for assessing the advantage of quantum algorithms, applied this tool to chemistry and deep learning, and estimated the rate of progress in large language models. Across each of these domains, analyzing progress requires leveraging the right framework to clearly capture the salient innovations of different kinds of algorithms.

Broadly speaking, we think analyzing algorithmic efficiency is a multifaceted problem which still requires new ideas and frameworks to properly capture. Models perform across many axes and their costs are multidimensional. To fully capture the efficiency of a model, we need better ways of measuring capabilities, training inputs, and pre-training/inference tradeoffs.

You can read the paper here. Stay subscribed to Mixture of Experts to get the latest updates about these research questions.

This post was written by Alex Fogelson. Zachary Brown, Sebastian Sartor, Lucy Yan, Hans Gundlach, and Neil Thompson provided editorial feedback. The authors of the paper are Hans Gundlach, Alex Fogelson, Jayson Lynch, Ana Trišović, Jonathan Rosenfeld, Anmol Sandhu, and Neil Thompson. For correspondence on the paper, please contact Hans Gundlach or Neil Thompson.

In practice, coordinating between GPUs involves other kinds of computational overhead, but the efficiency of the floating point operations would stay the same.

About 1013 through 1018 FLOPs.

Both scaling laws we find are of the form L = ACa, where C is pre-training compute, L is the loss, and both A and a are constants. Our ablation experiment changed the value of A, the multiplicative constant, to some greater A’, but left the exponent unchanged. Thus no matter the compute scale, ablating the cluster of algorithms implies a compute multiplier of (A’/A)1/a.

Our paper also breaks down the distribution of efficiency gains for each innovation individually, as well as their interaction effects.

This presents as an exponent shift in the scaling law. Earlier we showed that a mere multiplicative change yields a multiplier of (A’/A)(1/a). If the exponent shifts from a to a’, the result is a compute multiplier of the form (A’/A)(1/a) C(a’/a - 1), which is no longer constant and increases with compute scale.

Smaller models are often trained with less compute, though techniques like distillation make this analysis less straightforward. The next section discusses this briefly.

The reference-frame dependence issue is fascinatng, it's wild that the same sequence of models can look like zero algorithmic progress from one perspective and massive gains from another. This mirrors issues in classical algorithm analysis where comparing different complexity classes becomes reference-dependent. The 91% figure for scale-dependent gains really undercuts the conventional narrative about "brilliant researchers discovering clever new techniques." Most gains are actualy just bigger models exploiting properties that only emerge at scale.